As a Black woman of a certain age, how do you feel when you hear the plunky tinkle of a banjo? What associations does that sound stir in you?

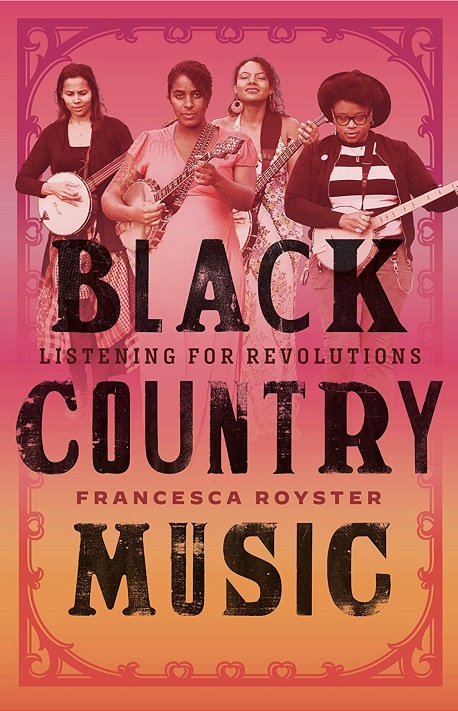

Francesca T. Royster is a professor of English at DePaul University in Chicago. She is the author of several books, including Sounding Like a No-No: Queer Sounds and Eccentric Acts in the Post-Soul Era and Becoming Cleopatra: The Shifting Image of an Icon. Her latest book, Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions (University of Texas Press, Austin, American Music Series, https://utpress.utexas.edu/9781477326497/), is an eye-opening challenge to how country music is defined, understood and received.

And, Dr. Royster plays the banjo.

The banjo is a direct descendant of about 60 West African instruments, including the ngoni, the xalam, and the ancestral instrument most closely resembling the modern banjo, the akonting. Just a few notes summon ghosts of Dixie. A white American man named Joel Walker Sweeney is credited with “inventing” the five-string banjo just prior to the Civil War, and Sweeney and his family created a popular traveling show that included rousing minstrel numbers performed in blackface. These associations understandably make many people cringe (plenty of white people included). The banjo, like all things associated with the American South, carries the scar and stigma of a past that much of America would rather forget, or simply deny. Points of reference included the movie Deliverance, and decades of television ads for Mountain Dew.

Just as Uncle Ben is now gone from his box of rice and Aunt Jemima has vanished from her syrup bottle, the banjo as talisman of country music was an early example of cancel culture. And yet, Royster’s book as well as her banjo-playing serves as a call to return home as well as a challenge. We caught up with Dr. Royster via Zoom where her office walls are poppin’ with the covers of classic R&B, soul, jazz, bebop, doowop, pop and funk LPs. With a warm smile, she said “Check out the Black Banjo Reclamation Project. It will blow your mind.” (She’s right: https://blackbanjoreclamationproject.org.)

“There is deep shame and pain that come up whenever we talk about the South,” she says, noting that her father, also a teacher of English, was a gifted percussionist who found his joy in patting out complex patterns on congas as a performer and session player in Nashville. “I picked up the banjo in the same spirit that I wrote this new book. It’s about exorcising that shame and pain. And also, it’s about excavating the truth, and reclaiming the African and African American contribution to country music.” There’s no denying the blues, she says, that emanated from the Mississippi Delta to lay the foundations for every musical form we identify as “American,” from ragtime to rap. Even the structure — what musicians call the 1, 4, 5, meaning the chord progression that forms the DNA of most contemporary pop music of all genres — is blues-based and thus inherently Black.

Royster writes, “The 1970s saw a kind of white backlash. Even when white country artists demonstrated a respect for Black music, they often left actual Black musicians out of the limelight. In this period, a new generation of white country artists who were interested in integrating soul, R&B, and funk into their music were credited for being experimental and expansive, while Black music was treated as the raw material for white creativity.”

In addition to the racial stigma, Boomers grew up with parodies of what being “country” meant. For a time, “country”-themed content dominated prime-time television, from the Glen Campbell and Johnny Cash musical variety shows, to the gently humorous regionalism of The Andy Griffith Show and Mayberry, R.F.D., to the truly insulting Hee-Haw (although the latter did showcase major country artists of the era, including Buck Owens), Green Acres, The Real McCoy’s, Petticoat Junction, and The Beverly Hillbillies, although, truth be told, lots of us loved hearing The Ballad of Jed Clampett so brilliantly picked and sung by Flatt and Scruggs during the credits. Self-respecting liberals of every complexion distanced themselves from anything with a down-home twang, in the process turning away from the legacy of poverty, race violence, and backward ignorance of everything below the Mason-Dixon line. Mostly-white rock fans boycotted the 1969 single release of The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down by The Band. Followers of Tom Petty protested the Florida rocker’s 1985 album release Southern Accents, which included the blistering cut called Born a Rebel, often performed against the backdrop of an enormous Confederate flag. (Petty later issued a formal apology for what he termed “a cracker relapse, and a lapse of sanity.”) And consider that, more recently, even The Dixie Chicks have dropped the “Dixie” from their band’s name.

Royster references historic field ethnographer Alan Lomax and other early 20th century music historians as creating an origin-story for country music that is misleading, misinformed, or at the very least, incomplete. What’s missing: the electrifying presence of Black musical genius. Lomax and his contemporaries focused on the deeply Anglo roots of many songs that found their way across the Atlantic to coal-mining country, relocating themselves in the isolated hills and “hollers” of Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia. While Scottish and Irish melodic structure permeates much early country music, especially the minor keys, lilting time-signatures, and nasal, modal tones that flavor bluegrass, country music is a far richer, funkier, more satisfying crazy-quilt hybrid than any single culture could have produced in isolation. The author also traces Tejano and Mexican rancheras and corridos, vaudeville and Tin Pan Alley song-making, and jazzy Jewish klezmer as still more bursts of flavor in this simmering cultural gumbo.

“Coming to terms with country music felt as dramatic as my own coming out as queer,” says Royster. “I understand why many Black people aren’t comfortable listening to, say, Merle Haggard’s Okie from Muskogee, or Lynyrd Skynyrd’s anthemic Sweet Home Alabama. But if we listen to country music as it is emerging today, there’s new spirit of inclusion and collaboration.” She’s an unabashed fan of Lil Nas X, citing the “yeehaw agenda” created by the young Black Dallas blogger Bri Malandro. “Black cowboys and Black cowgirls are talking back to present and historic erasure.”

Perhaps the sweetest re-introduction to country as one flowering of American roots music is the music of the incandescent Rhiannon Giddens, founding member of the Grammy-winning group, the Carolina Chocolate Drops. This Greensboro, North Carolina native plays banjo and fiddle as well as being a composer, songwriter, arranger, actor, and lead singer. In 2020, Giddens was named Artistic Director of the cross-cultural music organization Silkroads. Her 2018 album Songs of our Native Daughters on the iconic Folkways label is a painless (and illuminating) entry-point into what “country” music looks and sounds like today. Giddens has been quoted as saying, “People who have avoided country music all their lives sometimes think I’m Alicia Keys. Until they see my banjo, that is.”

#

Be the first to comment