Afro-Atlantic Histories

This exhibition is co-organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in collaboration with the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, Brazil, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Exhibition includes more than 100 artworks and objects which track the transAtlantic slave trade and its legacies in the African diaspora from a global perspective.

WHERE: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Resnick Pavilion, https://www.lacma.org

WHEN: Now through September 2023

THE TAKEAWAY: “Africa is Everywhere”

Divided into six sections, this complex exhibition tells the story without attempting any tidy reconciliation. The theme, not chronology, determines each of the six sections, so you can enter the exhibit at any point. It’s a non-linear blur of impressions and sensations, like a fever dream. Considering that the Middle Passage was a journey of 5,000 miles, begun in 1441 with vibrations persisting across the waters of time into the present moment, it serves the larger purpose that this exhibition is more of an immersion than a neat itinerary.

The sections are Maps and Margins, Enslavement and Emancipation, Everyday Lives, Rites and Rhythms, Portraits, and Resistance and Activism. Each section includes works from a broad spectrum of makers, Afro-descended, Caucasian, contemporary and colonial, as well as a mixed bag of media and materials. Video snippets in Portuguese make sense, since the slave trade began in Portugal, and Lisbon quickly became the initial center of the tragedy. A 3 minute and 26 second video, “Intervenção no Rio: Como sobreviver a uma abordagem indevida (Intervention in Rio: How to Survive an Improper Approach)” by AD Junior @adjunior_real, El Carvalho and Spartakus Santiago, is essentially “the Conversation,” created by these three Brazilian activists and digital influencers who advocate for the rights of Black people in their chaotic country. It’s an advice video giving tips for surviving the government occupation by armed troops in Rio’s favelas, along the lines of, “If you are Black, listen up…avoid going out of the house in the wee hours, carry the receipt for any expensive equipment, and never walk alone.” The brevity and directness of the video message is what’s chilling. No muss, no fuss, that’s how it is. The advice applies equally to the occupants of any police state.

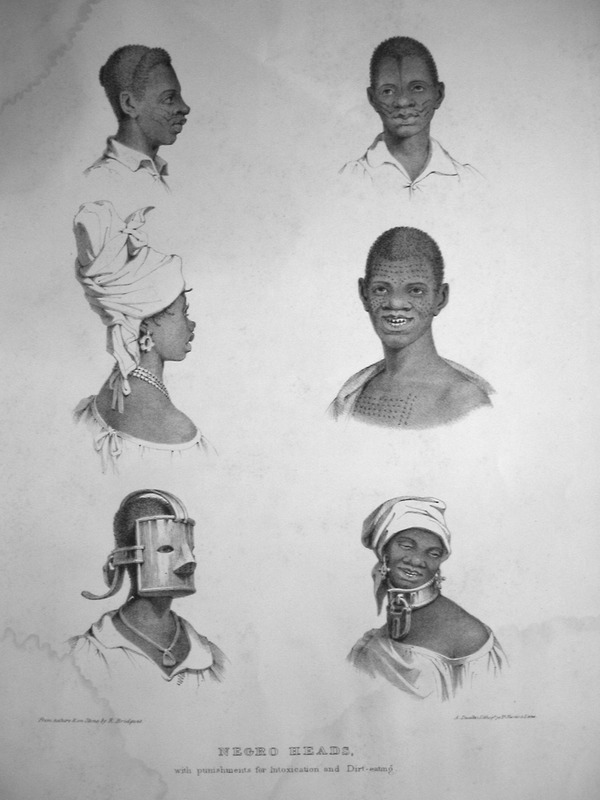

The wide variety of art forms is dizzying. Two items summarize the power of this content. One is an engraving by Richard Bridgens, a white man who moved from England to Trinidad where his wife had inherited a sugar plantation. Bridgens is sometimes called “The Artist of Slavery,” and yes, of course, he was the overseer of stolen African people who worked his cane fields. Bridgens was a formally trained architect, sculptor and furniture-maker, whose exquisitely carved and decorative, inlaid tables are treasured museum pieces, and he applied equal precision to his life drawings of life on the plantation.

The piece shown here is called “Negro Heads,” circa 1836, a grouping of life-drawings of enslaved people on the artist’s property. Two of these naturalistic portraits cause a sharp intake of breath. In one, a wide metal cuff with a lock encloses a sleepy-looking woman’s throat. Beside her, the face of a man is entirely hidden within a terrifying metal mask. The artist explains in a caption, “ …the tin collar is punishment for drunkenness in a female, while the mask is a punishment and preventative of dirt-eating.” University of Illinois history scholar Rana Hogarth has written extensively about geophagy (earth-eating) in her book “Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840.” The author observes that although the practice of eating dirt is found in many cultures, it is now most popular in modern-day Kenya and Cameroon, where bite-sized morsels of clay may be bought in local markets as snacks, sometimes flavored with black pepper or cardamom. And not coincidentally, the descendants of slaves in America continue the practice. Consider the website www.georgiawhitedirt.com, where one may purchase unprocessed kaolin, marketed as “…a wonderful novelty item (not for human consumption).” While nutritional deficiencies may be part of the explanation — pregnant women seeking to ease their cravings often are customers today — Hogarth and others suggest that the habit may be more nuanced as an expression of the profound loss of land, identity, and self.

An installation by revered Los Angeles assemblage artist Betye Saar is so subtle that it may be overlooked amidst the sequined Haitian drapos, feathers, and showier colors within this exhibition. Her piece consists of just a few homely elements which at first seem so familiar, then take on nightmarish realization. An old wooden ironing board, an old-time iron, a laundry-line stretched across the space, a white sheet slung over it to dry. On second look, the ironing board bears the floor plan of the 18th century British slaver, the Brookes. Superimposed over the tomb-shaped diagram is a drawing of a stereotypic Mammy figure. Then we notice that the rusted iron is chained to its spot, still threatening to brand a blister on stolen skin. And the sheet is more than mere bedclothes: embroidered white-on-white on the immaculate hem burn the three letters: “KKK.”

Check out this exhibit through September.

Be the first to comment