CHANGE-AGENT: Donna Walker-Kuhne

We are always changing. When we’re young, we may be oblivious to this fact. When our bodies are fresh and new, we may secretly believe that we are invincible and will live forever. By age 50, it’s likely that we’ve surrendered these ideas. The losses and changes accelerate with time, but for Renaissance woman Donna Walker-Kuhne metamorphosis is inevitable, and a cause for celebration.

The award-winning arts marketing consultant and Broadway producer is acknowledged as the nation’s foremost expert in audience development. Through a series of stunning professional, creative and spiritual transformations in every decade of life, her devotion to increasing access to the arts for multicultural communities has generated more than $23 million in developing programs for people of color and other underserved arts-lovers.

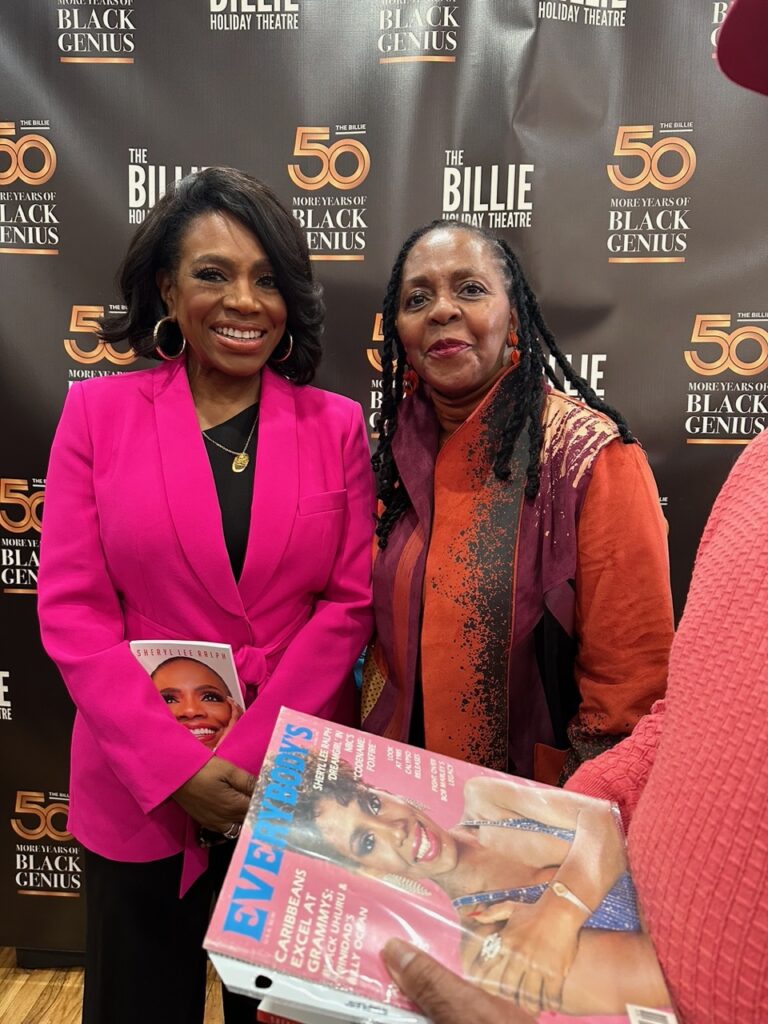

As the founder of Walker International Communications Group, Inc., She’s been central to the engagement of more than 22 Broadway productions including Aladdin, A Streetcar Named Desire, A Raisin in the Sun, Smokey Joe’s Cafe, Bring in da Noise, Bring in da Funk, Driving Miss Daisy and Ragtime. She has served as Vice President of Marketing and Vice President of Community Engagement at New Jersey Performing Arts Center and Director of Marketing for Dance Theater of Harlem, The Public Theater and The Apollo Theater. She also consults with numerous prestigious nonprofit arts organizations including Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, Harlem Week, and Santa Fe Opera. Donna currently serves as Senior Advisor, Community Engagement at New Jersey Performing Arts Center. Her second book, titled Champions for the Arts: Lessons & Successful Strategies for Engaging Diverse Audiences, hits the shelves this month (October). We caught up with her recently between meetings and speaking engagements in Queens, NY, where she laughed, “I’ve got my next five lifetimes planned out!”

It all began with dance. Seeing Swan Lake as a 5-year-old child in her native Chicago led Donna and her twin sister first to pointe shoes, and then to the study of traditional West African dance. This love of dance, paired with her family’s participation in Operation Breadbasket helmed by the Reverend Jesse Jackson, set the template for what was to come: a life of loving the performing arts, driven by an unflinching devotion to social justice. “These were the bookends to shaping my identity,” says Donna. “I am a daughter of the Great Migration. My parents moved to Gary, Indiana, then to Chicago from the South, to feel that Warmth of Other Suns, you know? We were a very tight-knit family, kept each other safe. I grew up on the South Side, about 10 blocks from Michelle Obama. We were warned to stay away from white people, and we didn’t trust them. When my dad died when I was 11, I started to hear my mother’s voice. Up until then, my mother didn’t vocalize political or social theory, but she began to speak, and my advocacy came from her.”

But a prescient sense of practicality by age 13-14 led Donna to decide that “…dance would most likely not be a source for a steady paycheck. So, I decided to go to law school,” and after graduating from college enrolled at Howard University School of Law. This dramatic pivot is but one of many which opened a daring path of self-challenge to Donna.

She loved it, collecting a coveted AmJur award for her excellence in Torts. But for a minute, the pressure got to her, manifesting in migraines and colitis, and she briefly took to her bed. Other than Torts, she was struggling in her studies. “Everything was falling apart. While I was lying in bed, I found the Buddhist prayerbook and beads that my then-boyfriend had given me on my nightstand, so I began to chant.”

Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. This is the chant of Soka Gakkai Buddhists, representing the ability to overcome any obstacle, and to experience joy in the process. She was back in class at Howard the next week, completing her studies, then graduated and moved to Brooklyn where she worked for the family court system as a litigator and prosecutor as the Assistant Corporation Counsel for misdemeanors by juveniles, circa 1980.

The awakening created by her embrace of Soka Gakkai led to further epiphanies, notably one right across the street from court. “I loved presenting in court,” she recalls. “But after the first year or so, I began to ask myself, what am I actually doing? My deepening Buddhist practice was making my purpose more clear. In my work with the courts, I realized that I was basically sending young Black men deeper into the violent and unjust criminal system.”

At the time, Donna was still studying dance, and so it wasn’t much of a stretch for her to look across the street to the Thelma Hill Performing Arts Center, named for the barrier-breaking dance innovator known lovingly as the Mother of modern Black dance.

This pivot led to a leap of faith with both feet. Fearlessly, she approached Arthur Mitchell, the first Black dancer with the New York City Ballet (NYCB), and later the founder of Dance Theatre of Harlem. Although Mitchell had never previously entrusted anyone as his assistant, he asked Donna to accept the high-profile role. “I used every skill I had,” she recalls. “I stepped into his skin.”

More pivots and awakenings followed. Later, as Director of Marketing for Dance Theatre of Harlem, Donna was invited to South Africa three months after the release of Nelson Mandela in 1993. The goal: to integrate South Africa’s Civic Theatre. “I walked into that room and there sat 13 white men. They did not look happy. In fact, they were hostile. I didn’t think I would make it out of there alive.” But she persevered, using what Buddhists call “soft power.” And the chickens came home to roost: “By the end, the white Afrikaans secretary who had been so very rude to me was serving me tea,” Donna says sweetly.

Another major transformation followed when she received what she believed was a prank phone call from a man who identified himself as George C. Wolfe. “My initial reaction when I listened to the message was, yeah, right. But I figured what the hell and called the number back.” It was indeed George C. Wolfe, the pre-eminent playwright and director of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, The Colored Museum, Angels in America and Jelly’s Last Jam. He had heard talk about Donna’s ability to bring young Black and Brown theatergoers to the box office and drive profits while raising the visibility of the work of BIPOC performers. He told Donna, ‘I’d like this place to look like a subway stop’– meaning a diverse population. She worked with Wolfe for nine years, and eventually made her move to Broadway as a marketer.

One of her innovations at The Public Theater was called “Free at Three,” an arts event held at 3 PM every Sunday at no charge. Making the decision to hold the event immediately after 9/11 was painful. “We decided, ‘Let’s do it anyway.’ I remember 300 people crowded into the space meant to hold 150. They were all so badly hurting, so in need of healing. Rita Dove read some of her poems, and the people stood, eyes closed, faces uplifted. I could literally see her words rolling down their faces like a balm. I had felt the healing power of the arts before, but I had never seen it before.”

The update: “Now I’m in the process of developing Town Halls around the country to celebrate local champions who bring the arts to the people through strategic partnerships and community engagement.” She says, “Now more than ever, we show our fearlessness and fight back with our art.”

What feeds the fire? “Half of my motivation is to pay the debt of gratitude to our legacy. Once you see yourself this way, it just never stops, as long as you have breath in your body. Yes, just do it– do it, and change the world.”

#

Be the first to comment